In order to bring the Samba – the most authentic Brazilian musical genre – into the Clube, there is nothing better that telling the story of the first samba song ever recorded of. The session took place in 1916 and the song was “Pelo Telephone” (Over the Telephone).

Format: MP3/ZIP

Size: 37,9 MB

If you enjoyed this story, consider becoming a member of the Clube da Música Autoral.

Go to: clubedamusicaautoral.com.br/subscribe and check out the benefits you get in exchange for your support.

Script: Gilson de Lazari

Voiceover: Gus Ferroni

Review: Camilla Spinola

Visual Art: Patrick Lima

Audio editing: Rogério Silva

Subscribe

Apple Podcasts

Google Podcasts

Spotify

Deezer

Amazon Music

Castbox

Podcast Addict

Pocket Casts

RSS

More Options

Contact us

Facebook

Twitter

Instagram

WhatsApp

Telegram

If you prefer, write a comment to us, or send an email to: clubedamusicaautoral@gmail.com

Playlist

Want to listen to the songs played in this episode? Check out the playlist on YouTube

Hi everyone. My name is Gus Ferroni. I’m an ESL teacher and a Portuguese/English translator speaking from São Paulo, Brazil.

I’ll be translating and narrating some episodes of the podcast Clube da Música Autoral.

Anyway, I’d like to welcome you all and explain why we chose this particular episode as the first one to be translated.

Well, this episode is about samba, the most authentic and original genre of Brazilian music and I’ve got to admit I’m a little bit nervous talking about samba. Samba in Brazil is like a religion. It’s sacred, and I’m not a samba guy, I’m a rock guy, but I have the utmost respect to this centennial institution that brought together energetic African percussion-based rhythm with the beauty and passionate Portuguese language and music.

So, from now on, to honor all the samba lovers around the world that don’t speak Portuguese, I’m proud to say that samba is officially the first episode of Clube da Música Autoral in English.

Well, where should we start off then? The classics, of course, obviously, after all there are amazing names like Beth Carvalho, Noel Rosa, Pixinguinha, Cartola, Clementina, Martinho da Vila, Zeca Pagodinho, Bezerra da Silva… wow, what an awesome dilemma!

We knew though that at the right time the answer would come along and so it did. Cocão, the guy responsible for the channel’s website, raised his hand, as he always does, and said: “Hey guys, somebody left a new comment on the page. We quickly took a look and found a suggestion from a listener called José Augusto Coelho Filho who, among other things, pointed out that we should talk about the first samba ever recorded, “Pelo Telefone” (which can be translated as “Over the Telephone”). It’s a samba from 1916, that carries amazing stories.

So, we thought: “of course, that’s it!” We’d already mentioned that song in Extra Episode #1 – The history of music.

Different from all the other songs covered in the previous episodes of the Clube, this one does not have a defined author. We will talk about several people who somehow contributed to the “Pelo Telefone” track.

Just one last thing before we dive into the stories behind this song: Go to your Facebook, Instagram, Twitter and YouTube. Find us there – That’s CLUBE DA MÚSICA AUTORAL (SPELL it out). Start following us to receive some extra content. And while you are there, check out some incredible photos.

And if you really enjoy these stories, and want us to keep investing more and more time and energy in them, give us your financial support and become an official partner. Go to www.clubedamusicaautoral.com.br/assine and choose the plan that best suits you.

Let’s go samba then? From now on, with all due respect and without being vague, we will tell the story of the first samba ever recorded: “Pelo Telefone”.

I’m a musician, a rock bass player, and I also know how to configure the sound of a rock band on a stage, you know? Set up the mics, operate the sound board, the monitors and mains, etc. But there was one gig I’ll never forget.

My band was playing a public event, on a big stage and halfway through our gig, I noticed the band that would play after us was a samba band. 10-15 guys with a mountain of instrument cases.

Right after we finished our gig, the head sound engineer asked us to get off the stage as fast as we could so that he could do the sound check for the samba band.

As we got off the stage, all 10 guys jumped on up and started figuring out where each one would sit. They looked very cool and confident while the sound technician positioned the microphones on each percussion and harmonic instrument. I wanted to know how they were gonna pull that off, so I stood by the sound board and noticed that he’d used up all 24 channels available.

All microphones in: Time to do sound check. Using the talk back microphone, he said:

“Hey guys. Let’s get on with it. We’re going to start with the ‘reco-reco’, ok? Reco-reco or dikanza is a scraper of African origin. It came from a region of Africa, present day Angola, and was originally made from a sawtooth notched cylinder made of bamboo or wood. In Brazil, it’s made of metal with springs attached to it and played with a metal stick. It’s pretty common in samba and in other Latin American music genres such as cumbia and salsa. I heard the sound it produced and thought to myself: “it sounds like a hi-hat, only shoots high frequencies”.

The next instrument was the timbal. In fact, timbales. Two metal drums, slightly conical and not so high, with only the top nylon head which is played with the hand. They also produce high frequencies with a lot of attack.

The third one was the rebolo, also known as tantã, a cylindrical hand drum from Brazil, created by a guy named Sereno, a samba player from Rio de Janeiro and one of the founders of the band Fundo de Quintal. It has a very low sound and sometimes substitutes the bass drum in samba ensembles.

Following that came the pandeiro that in English is known as the tambourine. This one even I knew of. It’s the most popular percussion instrument in Brazil, present in virtually every samba, choro, pagode, coco, baião, maracatu, capoeira, and the list goes on and on. It’s a cylindrical frame, pretty shallow with pairs of small metal jingles around it and one leather or synthetic head. It’s sound is quite balanced, producing a wide range of frequencies.

Once all the rhythmic instruments were checked, it was time for the harmonic ones. And the sound engineer decided to call the cavaquinho in. The cavaquinho, along with the pandeiro, is one the most iconic instruments in samba. It evolved from the Portuguese instrument called Braguinha, a miniature guitar and was adapted in South America to harmonize with African drums. It is important to note that, despite being a stringed instrument, the cavaquinho is played percussively, giving the samba a whole unique swing and charm.

The next instrument to be checked: the 7-string acoustic guitar.

It would be an ordinary nylon string guitar, if it weren’t for the extra bottom string – the seventh string. This string acts like a bass, and can be tuned in either C or B. The 7-string guitar is widely used in choro, but also fits perfectly in any samba ensemble.

The surdão player was patiently waiting, sitting in front of the stage, but before the sound engineer called him up, the vocalist came by and said they might also play two instruments:

One, it was the tamborim, that is quite different from the tambourine that everybody knows. This one is a mini drum, very shallow, that fits in the palm of the hand and is played with a drumstick.

The other one was the cuíca. A very intriguing instrument. Cuíca is a drum with a wooden rod attached to the center of the leather membrane, on the inside. The sound is obtained by rubbing the rod with a piece of wet tissue. The fingers on the head change the notes thus creating this unique and distinguishing sound. The cuíca was used in Africa by hunters to attract lions, since it somehow imitated the animals’ roars. Really Cool, isn’t it?

Finally, it was time for the surdão, the earthshaker. This one I knew quite well from the carnival parades. It consists of a massive bass drum with 26 inches of diameter and 24 inches of height. The surdão player, a 300-pound black fellow, gets up slowly and goes to his spot on the stage. Meanwhile the sound engineer whispers to me: “now it’s the moment of truth, bro”, and added “the surdão is the most important element of samba. It’s all about the bass”.

I thought to myself, “Replace the double bass? Whaaat?”

. Once the signal hit the mixing table, it produced a nasty feedback.

He asked to turn off the sound on the stage and leave only the sound of the PAs. The low sound was shaking the whole place up. He then said: “Not good enough”, and began tuning the head.

The perfectionism with which that musician treated that drum made me reflect on the importance of the surdão.

Many consider it to be the “heart of samba”. This earthshaking huge bass drum also has a rich history. It is a true Brazilian invention, created by Alcebíades Barcelos, who used a butter drum, rims and goat skin. The surdão debuted in the Carnival of 1928, in the Deixa Falar parade, the first Brazilian samba school. The same school that added the tamburim, the cuíca and the pandeiro to the sound. It was such a success that in the following year, all schools incorporated the “surdão” and the samba stopped being “tan tantan tan tantan”, and became “bum bum patíca bum bum bum pá”.

Back to our sound check, the surdão player finally shouted: “Okay, let’s go. Let’s do the voices now.”

All musicians got back up on the stage again, got their instruments and started playing them.

It was magical. Such an organic sound, so dynamic. I could hear everything. I looked at the band’s roadie who was nodding with approval. After some more adjustments to make sure all the musicians were listening to each other, the sound check was over.

That night, when I saw the audience smiling and dancing and singing along, I realized that that experience would change the way I saw music forever. As I mentioned earlier, I am a rocker and didn’t really dig my country’s musical roots. I admit and I’m a bit ashamed of it, but at that time I did pay more attention to American and English cultures. I don’t want to turn this into a dispute of which one is better, but after studying and learning more about Brazilian music, I also started to appreciate the history of my country as a whole, after all, we are talking about cultural treasures here. So, let’s go deeper in it. Cocão, rewind the tape a little bit more, cause I’m gonna tell the story about the origins of samba.

According to historian Cláudio Fernandes, samba comes from a mix of several musical elements, brought from Africa and from Europe to the city of Rio de Janeiro in the 19th century.

Samba derived from the ancient drumming brought by the Africans that were dragged to Brazil as slaves. These beats were generally associated with religious elements that formed some kind of ritual communication among the black communities through music and dance, percussion and body movements. Those rhythms gradually incorporated elements from other types of music.

From the 19th century onwards, the city of Rio de Janeiro, which had become the capital of the Colony and later the capital of the Empire, started to experience a huge influx of black people coming from all over the country, especially from Bahia. It was in this context that several clusters of people that observed the Yoruba religions started to spur in the city center, mainly around the area of Praça Onze. This was the landscape where the first samba circles pop up, mixing the elements of African beat with polka and maxixe.

The word samba refers, basically, to fun and party. However, over time, it also embraced the battle between the genre experts; the battle between those who could improvise the verses in a samba circle better, leading to one of the most relevant subcategories of samba in Rio: the Partido Alto.

The word samba probably comes from the Quioco ethnicity, in which samba means to hop like a goat, to play around, to have fun. Some say that it comes from semba, which means bellybutton or heart. This is the term applied to bridal dances in Angola characterized by umbigada, (which can be translated as a belly button dance), a sort of fertility ritual. In Bahia, there was a kind of samba circle dance in which the men played the instruments and the women danced, one at a time. The samba circle became the trademark of the Rio de Janeiro samba, with the elements of improvisation and choruses sung and repeated in groups. At the turn of the 19th century to the 20th century, samba was consolidated as the dominant popular musical genre in the suburbs and, later, in the hills of the country’s capital city. Two samba dancers became very popular around that time. One was João da Baiana (1887-1974), whose mother came from Bahia and was known as Tia Perciliana de Santo Amaro de Purificação, who recorded the samba “Batuque na Cozinha” or “Drumming in the kitchen.”

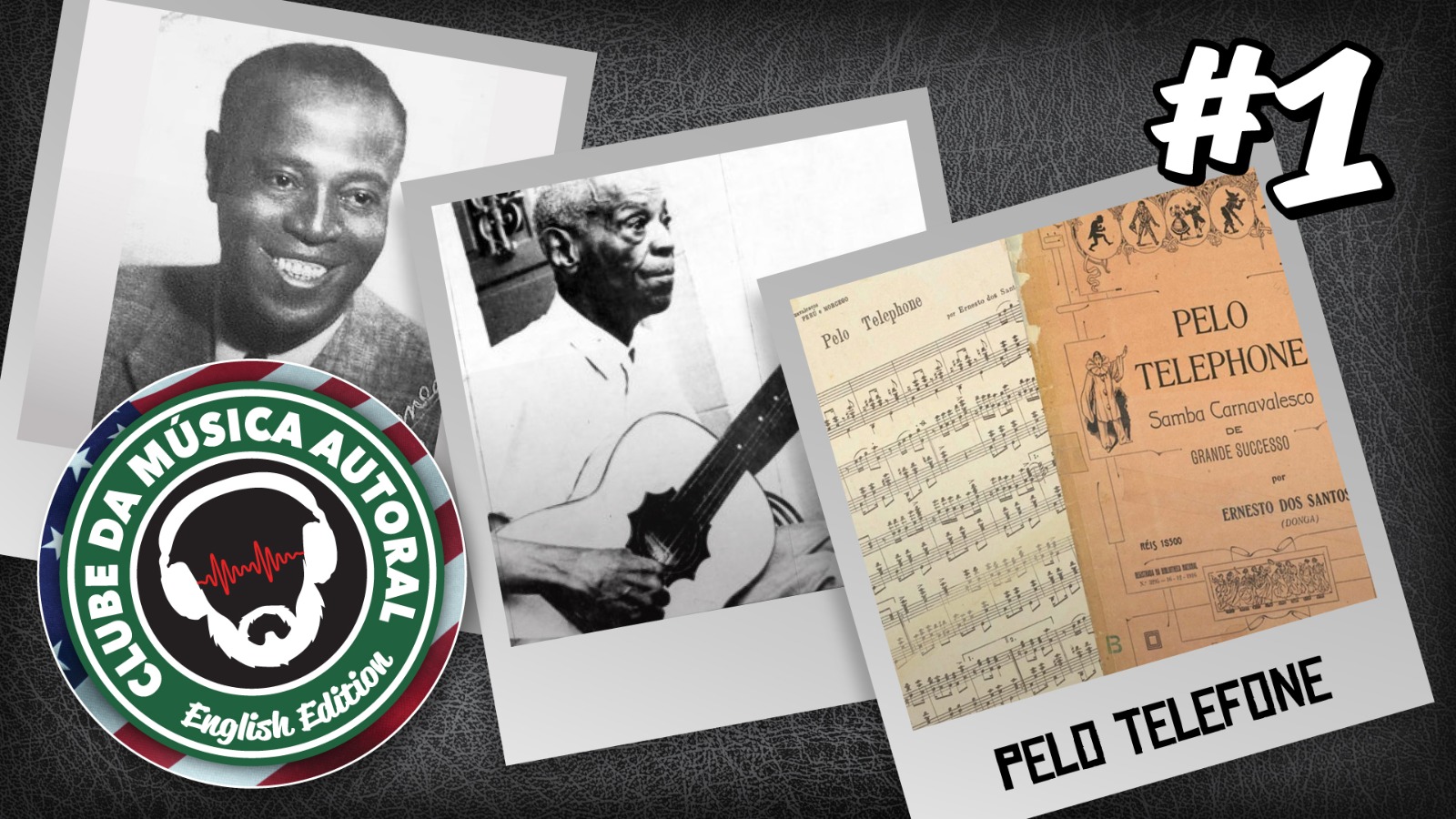

The other one, is the guy who composed the song that names this episode of the Clube: Donga recorded, on November 27, 1916, what came to be known as the first samba ever recorded: “Pelo telefone”.

This is the original register of the song. There are controversies about who actually wrote it, but Donga is definitely the most referred name, alongside Mauro de Almeida. The singer whose voice we hear in the recording is Bahiano, accompanied by the Casa Edison’s choir. The recording gear, as you might expect, is totally archaic. In Brazil, the acetate discs were produced only by Casa Edison, the only place with such cutting-edge technology. And, it is worth mentioning that only a handful of people in Brazil owned a gramophone to listen to the discs after they were recorded, which made this kind of business ultimately quite unprofitable.

Another interesting fact is that all Casa Edison’s recordings came with a little introduction before the song. Listen up.

November 27, 1916. The day samba was born. But which samba are we talking about? Samba as a popular tradition, or a specific samba song? It’s the latter, of course, as this date marks the launch of this registered and celebrated composition as a founding landmark of a musical genre that dates to a way distant past.

Researchers of popular music found that, on November 6th, 1916, a certain musician, Ernesto Joaquim Maria dos Santos, A.K.A. Donga (born in 1889 and died in 1974), applied to register the composition “Pelo Telefone” at the National Library’s Copyrights. Donga put down his name as the sole composer of the song, which he described as a “carnival samba”.

Ten days later, Donga attached a statement to the documentation stating that “Pelo Telefone” had been performed at a show on October 25th, 1916 at Cine-Teatro Velho. On November 27th, 1916, the National Library registered the work, and gave it the number 3,295.

Another curious note is that, in order to be registered, the composition needed to be presented as sheet music. Donga, who didn’t know how to write music, asked his friend and flutist Alfredo da Rocha Viana, better known as Pixinguinha, to transcribe it for the piano.

One of the several versions of its lyrics, in part attributed to the journalist Mauro de Almeida, who was also the carnival chronicler Peru dos Pés Frios in the newspaper “A Rua” – made a reference to a case that became quite famous in the streets of Rio de Janeiro:

In 1913, two reporters from the newspaper “A Noite”, Castelar de Carvalho and Eustáquio Alves, set a trap. They wanted to prove that the chief of police, Mr. Aurelino Leal, was just pretending to prohibit roulette gambling.

The report came out and drew attention to the episode. Of course, without knowing these facts, the song verses don’t make much sense, but after analyzing the newspaper article, we come to understand that: “The chief of police / Over the telephone / informed that, instead of putting an end to the prohibited gambling, let everyone know / That in the Carioca square / There is a roulette…”

Donga played the guitar. His father was a construction worker and his mother was Tia Amélia, one of the Bahia women who threw electrifying parties in her house with plenty of feijoada, cachaça and music. The gatherings were filled with singing and drumming and took place on Saturdays. At a certain point, during the party, they started singing and improvising funny lyrics about what was going on in their daily lives.

As a matter of fact, the name of those parties was samba, or roda-de-samba (samba circle) and on a certain Saturday someone threw those popular phrases about the chief of police in. The people used to put together verses and melodies from other folklore songs and thus those words were referred to as “Pelo Telefone”.

It’s evident that Donga also had part in it, but the thing is that he registered the entire song under his name alone. After registering it, he took it to Fred Figner, the American businessman born in the Bohemian region who owned Casa Edison, which was located on the number 107 of Ouvidor Street.

Founded in 1902, Casa Edison was a store that sold gramophones, typewriters and other high-tech gadgets. Figner also produced and sold 76-rpm speed discs and held a massive catalog of Brazilian popular music.

At that time, copyright for phonographic reproduction was not regulated in Brazil. But Figner liked to buy the compositions to record them. He had been doing this since he arrived in Brazil 20 years earlier. Sidenote is that he used to pay almost nothing for the songs – something around 10,000 reis for each song (which would be worth around US$50 with today’s money) and the track became his for life.

It was with Figner, as a patron, that Manuel Pedro dos Santos, Bahiano (born in 1870 and died in 1944), who was the most popular singer in Brazil back then, recorded “Pelo Telefone”, on a 76-rpm disc, under the Odeon label.

The recording took place at Casa Edison’s studio; a zinc shed built at the back of the store. Through the original recording, it is possible to feel the joyful and chaotic atmosphere that took over the environment and it is worth remembering that everything was captured on a single microphone. In other words, if there was an instrumental solo, the musician had to walk up to the microphone in order to be heard among the arrangement. And not only that, but there was usually a choir made up of high-pitched voices, that means that the main singer needed to stand way closer to the microphone to get proper volume and definition.

The record labels used to launch the new songs early in the calendar year, so that everyone would get to know them before Carnival. “Pelo Telefone” was no different.

The “carnival samba” was launched at the headquarters of the Clube dos Democráticos, in the district of Lapa, on January 19th, 1917, and was a major hit at that year’s Carnival.

Donga knew that some people would complain about the authorship of the song and thus tried to avoid it. Sinhô said he was the author of the chorus and accused Donga of stealing the collective improvisation.

Other composers, closer to Donga, preferred to remain silent. And he never confessed to the trickery.

The fact is that, as of that point, samba entered the radar of the music industry as a viable and popular product. The success of “Pelo Telefone” was at the heart of a dispute to define who’d compose the best samba for the following carnival. A decade later, this dispute had taken on another dimension between Donga’s and Sinhô’s teams, formed respectively by the traditional practitioners of chula raiada and the more modern urban samba musicians, who worked in the magazine theater. Samba, as a song, incorporated a linear logic, with beginning, a middle portion and an ending, mixing lyrics that sprouted from the day-to-day life.

The healthy battle between tradition and progress has persisted up to today. Fact is “Pelo Telefone” entered history as the “first samba ever recorded”, although there are also controversies about that as well. Nevertheless, the two reasons why the song drew so much attention were its success in that year’s carnival and this century-long discussion around intellectual appropriation.

The samba we know and love from today, even the one tagged as “root samba”, came up from the rivalry between Donga and Sinhô. The style they created was respected and revered, composed by hundreds of other musicians and shared as a product of popular culture. So much so that the traditionalists Pixinguinha, Donga and their colleagues, ended up adapting to modern samba when they went off to Paris to launch the group Os Oito Batutas, in 1922.

Great story, wasn’t it? After them, came Noel Rosa, Carmem Miranda, Ary Barroso, Dorival Caymmi… and so on and so forth. But, we’ll leave that for another episode.

Before I go, I must reinforce our deepest thanks to the directing members of the Clube … (inclui os nomes em português???)

They are more than members; they are directors at the Clube who help us keep this mission of keeping great stories behind our beloved music alive. If you want to become a partner, visit our website www.clubedamusicaautoral.com.br/assine and learn more about the advantages you get in exchange for your support.

Also, follow us on social networks. We always post photos, videos and other stories behind the music. We are on Instagram, Facebook, YouTube and Twitter (Telegram). Search for Clube da Música Autoral (SPELL), and be part of this Club.

If you like samba, you’ve probably already heard the version of “Pelo Telefone”, recorded by Martinho da Vila. In fact, many mistakenly believe that the song is his. And, it is amazing to realize that, even more than 100 years later, the song can’t be left out of any good samba gathering. That’s why we say goodbye with this live version, featuring Martinho accompanied by Tunico da Vila.

The production and original script from Clube da Música Autoral is from Gilson de Lazari, the editing is by Rogério Cocão Silva and the translation and narration in English is mine: Gus Ferroni.

It was a pleasure talking about music with you. Catch up with you later.

Aprovadissimo a versão em inglês!

Gostei muito e estou ansioso pelo próximo episódio!